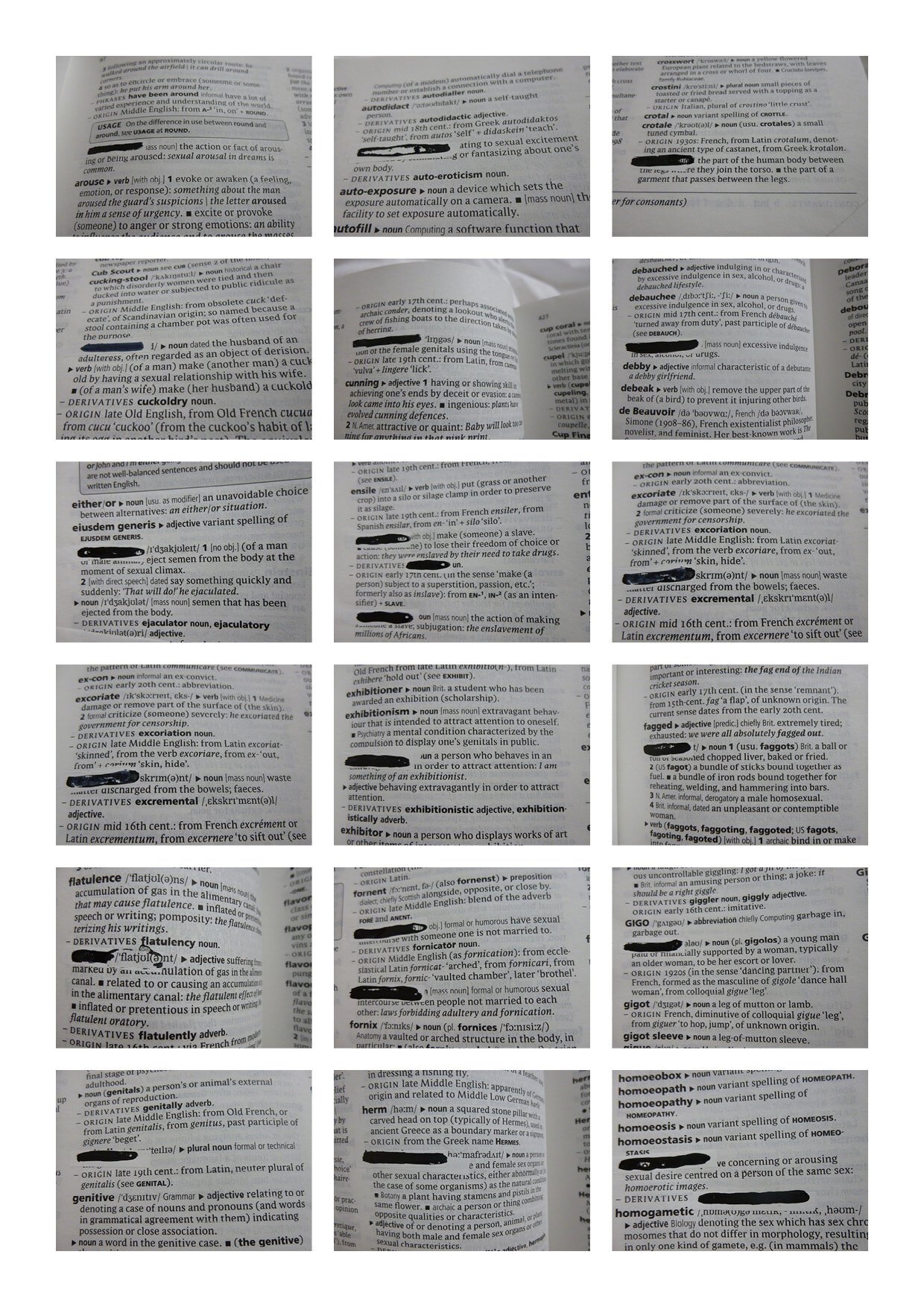

Recording language is not neutral; instead it reflects the cultural and social ideologies of the culture. Any dictionary takes into account and makes decisions on matters such as dialectical, scatological and taboo terms and whether to include new terms. Taboo terms have always been a problem for dictionaries. One of the first dictionaries, created by Cockeram in 1590, made sure that it attempted to distinguish between “vulgar words” and “refined and elegant language”. Other dictionary makers have been less polite and just ignored anything that they felt was offensive: Samuel Johnson, renowned dictionary maker, did not include anything that he felt would offend and Webster excluded any words that had sexual or excremental meanings. “Fuck”, for example, first appeared in a major dictionary in 1965 and for a very long time did not have a definition that included that it meant sexual intercourse although it has had this meaning since medieval times.

But dictionaries are being used and compiled in a different way than they were when Samuel Johnson wrote his. It is becoming rarer and and rarer for someone to take a dictionary off a shelf, look up a word and then write the correct one down. The dictionary, as a book, is becoming obsolete, just like CDs, videos and cassettes. Instead dictionaries are much more integrated in how we going about writing: uncertain of a word, if it is typed in incorrectly autocorrect will give a list of options as to what it might be. But there are gaps where, when words are felt by operating systems to be offensive, nothing is suggested.